President Clinton’s Remarks at the Funeral of Congressman John Lewis

Ebenezer Baptist Church

Atlanta, Georgia

July 30, 2020

As Prepared for Delivery

Thank you very much. First, I thank John-Miles and the Lewis family, and John’s incomparable staff, for the chance to say a few words about a man I loved for a long time. I am grateful to Pastor Warnock to say it in Ebenezer, a holy place sanctified by both the faith and the works of those who have worshiped here. I thank my friend, Reverend Bernice King, who stood by my side and gave a fascinating sermon in one of the most challenging periods of my life.

I thank President and Mrs. Bush and President Obama. I thank Speaker Pelosi, Representative Hoyer, and Representative Clyburn—who I really thank for, with the stroke of a hand, ending an intrafamily fight within our party, proving that peace is needed by everyone.

Madam Mayor, thank you. You have faced more than a fair share of challenges in these last few months, and you have faced them with candor and dignity and honor. And I thank you for your leadership.

I must say, for a fellow who got his start speaking to chickens, John has gotten a pretty finely organized, orchestrated, and deeply deserved sendoff this last week. His homegoing has been something to behold.

I think it’s important that all of us who loved him remember that he was, after all, a human being. A man like all other humans, born with strengths that he made the most of when many don’t. Born with weaknesses that he worked hard to beat down when many can’t. But still a person. It made him more interesting, and it made him, in my mind, even greater.

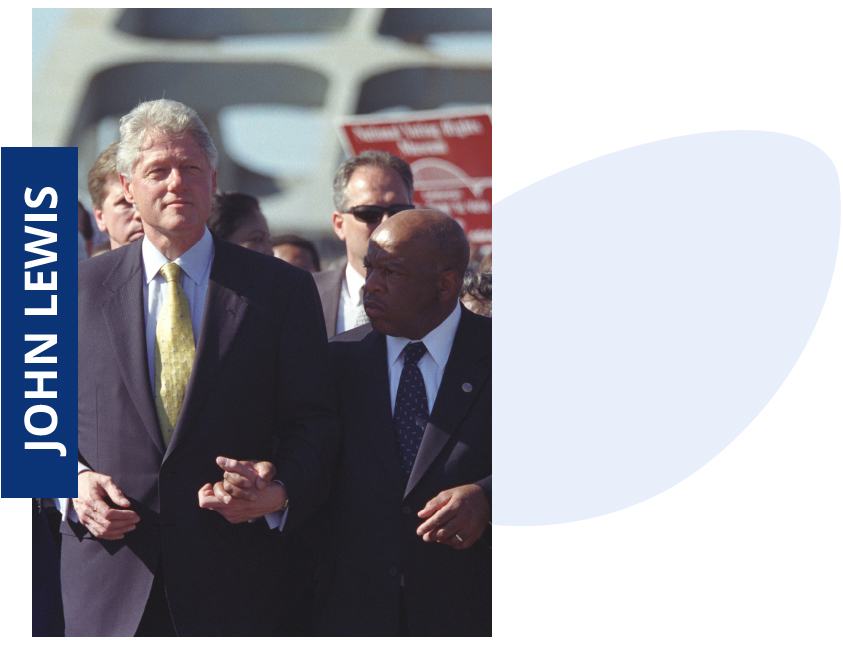

Twenty years ago, we celebrated the 35th anniversary of the Selma March, and we walked together along with Coretta and many others from the movement who are no longer with us. We are grateful for Andy Young, Reverend Jackson, Diane Nash, and many others who survive. But on that day, I got him to replay for me a story he told me when we first met, back in the 1970s. I was just an aspiring Southern politician and hadn’t yet been elected governor, and he was already a legend.

I said, “John, what’s the closest you ever actually came to getting killed doing this?” And he said, “Well, once we were at a demonstration, and I got knocked down on the ground and people were getting beaten up pretty bad. And all of a sudden, I looked up and there was a man holding a long, heavy piece of pipe. And he lifted it and was clearly going to bring it right down into my skull. At the very last second, I turned my neck away, and then the crowd pushed him a little bit, and a couple seconds later I couldn’t believe that I was still alive.”

I think it’s important to remember that. First, because he was a quick thinker. And second, because he was here on a mission that was bigger than personal ambition. Things like that sometimes just happen. But usually, they don’t.

I think three things happened to John Lewis long before we met and became friends that made him who he was.

First, the famous story of John at four with his cousins and siblings—more than a dozen of them running around their little old wooden house as the wind threatened to blow the house off its moorings, going to the place where the house was rising and all of those tiny bodies trying to weigh it down. I think he learned something about the power of working together. Something that was more powerful than any instruction.

Second, nearly 20 years later when he was 23—the youngest speaker and the last speaker at the March on Washington—and he gave a great speech urging people to take to the streets. He knew, as the saying goes, “Well, we have to be careful how we say this, because we are trying to get converts, not more adversaries.”

Just three years later, he lost the leadership of SNCC to Stokely Carmichael. It must’ve been painful to lose, but he showed as a young man, there are some things that you cannot do to hang on to a position—because if you do them, you won’t be who you are anymore. We’re here today because he had the kind of character he showed when he lost an election.

Then there was Bloody Sunday. He figured he might get arrested. And this is really important, for all the rhapsodic things we all believe about John Lewis. He had a really good mind, and he was always trying to figure out, “How can I make the most of every single moment?”

So, he’s getting ready to march from Selma to Montgomery. He wants to get across the bridge. What do we remember? He cut quite a strange figure. He had a trench coat and a backpack. Now young people think that’s no big deal, but there were not that many backpacks back then. And you never saw anybody in a trench coat, looking halfway dressed up, with a backpack. But John put an apple, an orange, a toothbrush, and toothpaste in the backpack to take care of his body, because he figured he would get arrested. And two books to feed his mind: one, a book by Richard Hofstadter on America’s political traditions; and one, the autobiography of Thomas Merton, a Roman Catholic, Trappist monk who was the son of itinerant artists, making an astonishing personal transformation. What’s a young guy, who is about to get his brains beat out, and planning on going to prison, doing taking that? I think he figured that if Thomas Merton could find his way, and keep his faith, and believe in the future, then he, John Lewis, could too.

So, we honor our friend for his faith, and for living his faith—which the Scripture says is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen. John Lewis was a walking rebuke to people who thought, “Well, we ain’t there yet, and we’ve been working a long time. Isn’t it time to bag it?” He kept moving. He hoped for, and imagined, and lived, and worked, and moved for his Beloved Community.

He took a savage beating on more than one day. And he lost that backpack on Bloody Sunday. Nobody really knows what happened to it. Maybe someday, someone will be stricken with conscience and give some of it back. But what it represented never disappeared from John Lewis’ spirit.

We honor that memory today because as a child he learned to walk with the wind, to march with others to save a tiny house. Because as a young man he challenged others to join him with love and dignity to hold America’s house down, and open the doors of America to all its people. We honor him because in Selma, on the third attempt, John and his comrades showed that sometimes you have to walk into the wind, and with it, as he crossed the bridge and marched into Montgomery. But no matter what, John always kept walking to reach the Beloved Community.

He got into a lot of good trouble along the way, but let’s not forget he also developed an absolutely uncanny ability to heal troubled waters. When he could’ve been angry and determined to cancel his adversaries, he tried to get converts instead. He thought the open hand was better than the clenched fist.

He lived by the faith and promise of St. Paul, “Let us not grow weary in doing good, for in due season we will reap if we do not lose heart.” He never lost heart. He fought the good fight and he kept the faith.

But we got our last letter today on the pages of The New York Times. “Keep moving.” It is so fitting that on the day of his service, he leaves us our marching orders. Keep moving.

Twenty years ago, I came here after the Selma March to a big dinner honoring John and Lillian. And John-Miles, you had a big Afro, and it was really pretty. Your daddy was giving you grief about it, and I said, “John, let’s not get old too soon. I mean, if I had hair like that, I’d have it down to my shoulders.”

But on that night, I was almost out of time to be president, and people were asking me, “Well, if you could do one more thing, what it would be?” or, “What do you wish you’d done that you didn’t?” All that kind of stuff. And when someone asked me that that night, I said, “If I could do just one thing—if God came to me tonight and said, ‘OK, your time is up, you gotta go home, and I’m not a genie, I’m not giving you three wishes. One thing, what would it be?’—I would infect every American with whatever it was that John Lewis got as a 4-year-old kid and took through a lifetime to keep moving, and keep moving in the right direction, and keep bringing other people to move. And to do it without hatred in his heart, with a song to be able to sing and dance.” As John’s brother Freddie said in Troy, keep moving to the ballot box, even if it’s a mailbox, and keep moving to the Beloved Community.

John Lewis was many things. But he was a man. A friend in sunshine and storm, a friend who would walk the stony roads that he asked you to walk, who would brave the chastening rods that he asked you to be whipped by. Always keeping his eyes on the prize, always believing none of us will be free until all of us are equal.

I just loved him. I always will. And I’m so grateful that he stayed true to form. He’s gone up yonder and left us with marching orders. I suggest, since he’s close enough to God to keep an eye on the sparrow and us, that we salute, suit up, and march on.

“I think it’s important that all of us who loved him remember that he was, after all, a human being. A man like all other humans, born with strengths that he made the most of when many don’t. Born with weaknesses that he worked hard to beat down when many can’t. But still a person. It made him more interesting, and it made him, in my mind, even greater.” — President Bill Clinton

★